I want to be able to connect to the environment using Visual Studio Code, so first we need to create a SSH key:

ssh-keygen -t rsaWe need a configuration YAML, replace <generated ssh-rsa key> with the above key, saved as cloud-init.yaml:

groups:

- vscode

runcmd:

- adduser ubuntu vscode

ssh_authorized_keys:

- ssh-rsa <generated ssh-rsa key>Assuming you’ve got Multipass installed (if not sudo snap install multipass) then:

multipass launch mantic --name ubuntu-cdk --cloud-init We’ll come back to Visual Studio Code later but first lets set everything up in the VM. We need to install aws-cli which I want to use with SSO (hence why we installed Mantic).

multipass shell ubuntu-cdk

sudo apt install awscli

aws configure ssoFollow the prompts and sign in to AWS as usual. Then install CDK:

sudo apt install nodejs npm

sudo npm install -g aws-cdkAlmost there, lets bootstrap1 (provisioning resources needed to make deployments) substituting the relevant values:

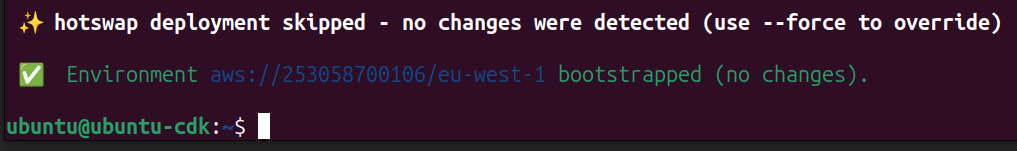

cdk bootstrap aws://<account>/<region> --profile <profile>You should see a screen like this:

Create a new CDK application by creating a new folder, changing into it and initialising CDK:

cdk init app --language python

source .venv/bin/activate

python -m pip install -r requirements.txtAnd that’s about it, except for Visual Studio Code. You’ll need to install Microsoft’s Remote-SSH extension:

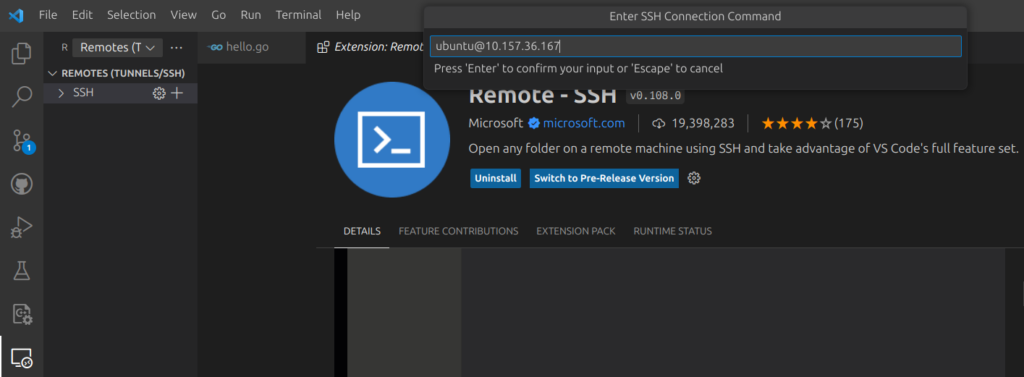

You can get the IP address from multipass list, then in Code add a new SSH connection using ubuntu@<ip>:

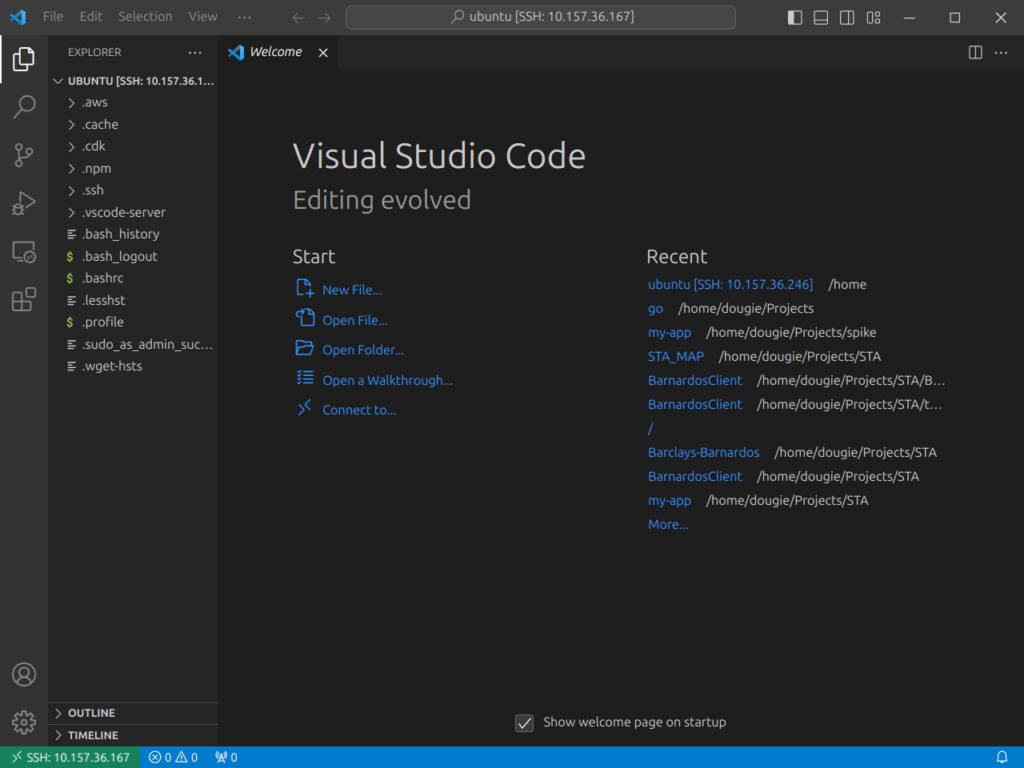

Accept the various options presented and you’re there!

- Bootstrapping provisions resources in your environment such as an Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3) bucket for storing files and AWS Identity and Access Management (IAM) roles that grant permissions needed to perform deployments. These resources get provisioned in an AWS CloudFormation stack, called the bootstrap stack. It is usually named CDKToolkit. Like any AWS CloudFormation stack, it will appear in the AWS CloudFormation console of your environment once it has been deployed. ↩︎